Tryphena Moore Crute Mathews

By Jack Schley

Tryphena was the first-born of many children that came to the Moore home. From an early age, she developed a sense of responsibility as she helped her mother with the care of her ever-expanding family. When Tryphena was about nineteen, she married Samuel Crute, a young planter who had moved to Georgia from Louisiana. This is the history of a remarkable southern woman.

This was a woman who labored in love only to lose all but her own life. She endured a most extreme and unnatural scenario of tragedy that no parent should ever have to experience. This all-consuming fire could have forged her into a hammer of destruction; instead, it created an anvil of strength and endurance for all that shaped the community around her. Tryphena was named after a woman of Biblical times, whom the apostle Paul described as one who “labored in the Lord.” Throughout her life, Tryphena’s actions showed that she was deservant of this ancient name. Tryphena was born in 1823 on the plantation of John B. Williams, her grandfather, in Crawford County, near Roberta, Georgia. Her parents were George and Rachel Williams Moore. She was one of eleven children, and at the age of nineteen, she married Samuel Crute of Louisiana. The newly wed couple made their home together near the Moore family land. Over time, Tryphena and Samuel had three sons and one daughter that were born into a comfortable home surrounded by a loving family. George and Rachel Moore were thrilled that Tryphena had chosen to make a life near them, but two of their elder children had also married and moved away from Robley, the family farm. As these two parents began to predict the future for their remaining eight children, who were all of, or around, marrying age, they could not bear the thought of living apart from them.

Mr. Moore determined that, in order to prevent his children from moving away, he would have to give enough of his own surrounding land to each child, as an incentive to keep them close by. This could not be accomplished at Robley, however, as land was expensive and George’s thirteen hundred acres was not enough to support a family for each of his children. He had to look beyond his lands in Georgia.

The answer came with the formation of Texas as a state. Land was abundant and cheap there. Samuel and Tryphena Crute agreed, along with the other eight, unmarried children, to make the move. Mr. Moore purchased a large tract of land near Anderson in Grimes County, Texas, and sent two of his sons, James and George, Jr, ahead of the family to prepare for their arrival.

Once in Anderson, James and George, who were both in their late twenties, along with a team of their father’s African slaves began to clear the land. A large house was to be built for all of the family, along with cabins for the slaves, and barns for the livestock. Back in Georgia, the family prepared to move. The Robley plantation was sold, and all of the household and farm possessions were loaded onto wagons while the family resided in Knoxville, Georgia. It was there that young James Moore returned from Texas to bring his parents, siblings, his sister’s family, and seventy-two of his father’s slaves to the new farm out west. There were fifteen members amongst the Moore and Crute families making the journey. The migration formed a long wagon train, loaded with all their family possessions that would be needed for life in Texas. In one wagon, a false bottom was created below the main bench where $30,000 in gold coins was concealed because gold was the only currency accepted in Texas at the time.

The family departed from Knoxville, Georgia on January 23, 1854, headed for Montgomery, Alabama, then to Mobile, and on to Galveston, Texas by steamship. By early February, the family had reached Galveston. The fully loaded wagons were rolled off of the ship, and the family began traveling again toward Anderson. They were not far outside of Galveston when they stopped to make camp for the night. They found an abandoned cabin along the road that was empty, except for a pile of discarded clothes. The garments were a little dirty but seemed almost new, so the slaves picked out items from the pile to bring on the rest of their journey.

The next day, many of the slaves were violently ill. Fearing contagion, Mr. George Moore pushed his family on towards Anderson, leaving his wife and two of their sons to care of the sick. By the next day, many of the sick slaves had died. Mrs. Rachel Moore loaded everyone up and began traveling in the direction of her family. Along the way, her twenty-year-old son, Julius, became ill and died in the carriage outside of Houston on February 10, 1854.

When Rachel caught up to her family, they were encamped in another abandoned log cabin along the road three miles outside of Anderson. The cabin was a single room that was sixteen by eighteen feet in size. Mattresses from the wagons had been unloaded and thrown on the floor. On the mattresses were her other children and grandchildren; all gravely ill.

The ailment was asiatic cholera. There had been an outbreak in Galveston just prior to the family’s arrival. The bacteria causes severe dehydration, leading to death in a few hours or a few days. It is a painful and messy manner of death. Mrs. Tryphena Moore Crute and her father George Moore, were doing everything they could to comfort their sick children because comfort was all they could attempt to provide. On February 12, two of the Moore children, William and Rachel, both died in the cabin. They were in their early teens. The next day, George Moore, Sr. was standing in the doorway to the house where his family lay dying when he noticed his own finger nails turning purple. He sent urgently for a lawyer from Anderson while he gathered around his remaining children. The lawyer, a Mr. J. Barnes, arrived to the cabin and later described it as, “…the most heart-rendering scene that I have ever heard of, and God forbid it should ever be my unhappy lot to witness the like again.” Mr. Barnes wrote George Moore, Sr.’s will as the man quickly fell ill into death.

While Mr. Moore conveyed his final wishes, his young grandson went from playing in the front yard to moaning on one of the mattresses on the cabin floor. Tryphena tended to him and the lawyer overheard the conversation between a mother and her child, “Mother, are all of my little brothers and sisters gone to Heaven, but me?” “All but my baby, son.” “Well Ma, you must come and father too.” Finally, “Oh! Mother meet me in Heaven.” Tryphena and Samuel’s three sons died that day, leaving only their one year old daughter. Samuel, himself, became very sick but rallied and was able to help Tryphena with the care of their remaining children.

George Moore, Sr. died shortly after signing his will. Death came over the family, “like a flood.” There were deaths amongst the slaves every day with as few as thirty-two of the original seventy-two already dead, and more dying. Mrs. Rachel Moore became very weak from nursing her family and had to lie down. As she watched her daughter, Tryphena, care for the remainder of the family, she called to her, “…lie down and rest. I will call you when I need you.” Tryphena dropped down on the mattress beside her mother. When she awoke, her mother’s arm was wrapped around her, but her mother was dead.

By February 19, thirteen family members were dead, leaving only Tryphena, her husband Samuel, and their infant daughter. That day, they departed the cabin for the family farm three miles away. They arrived, greeting Tryphena’s brother George, Jr. He had stayed on the farm to receive his large family, but only three had made it. That night, Samuel Crute grew weak again, and passed. Tryphena was relieved to still have her daughter, but the measles swept through Anderson, and the infant child died only a month after surviving the cholera outbreak.

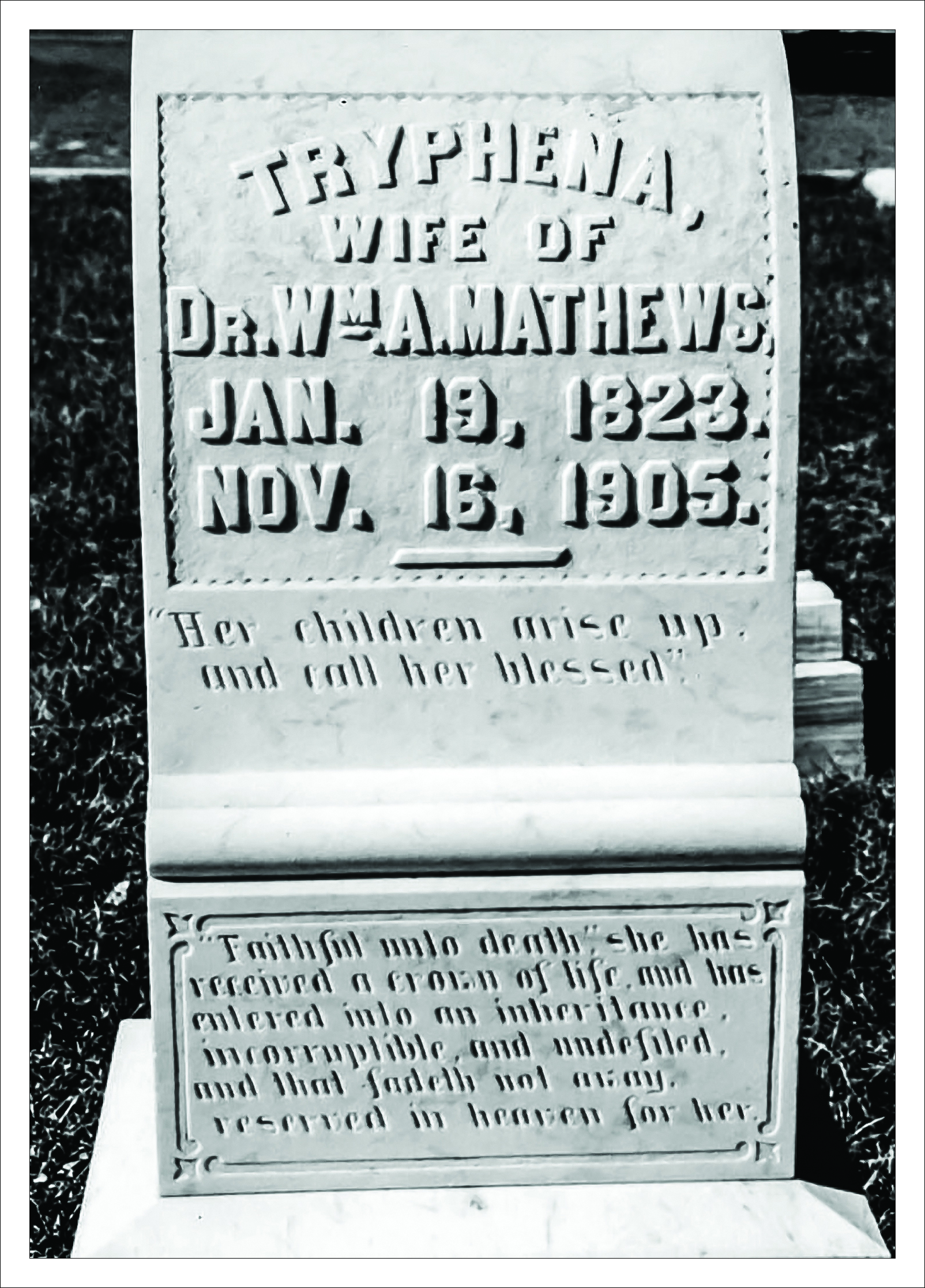

Overcome with grief and loss, Tryphena returned to Georgia. She had lost her parents, six brothers, one sister, her husband and four children; almost all in about ten days. She eventually remarried to Dr. William Asbury Mathews, and Tryphena had another three sons and one daughter, just as she had before. Dr. Mathews was a Methodist minister, and through him she found a purpose in her life. She became devoted, “unsparing(ly) in her ministries in the church and the community.” They made their home in Fort Valley, Georgia.

Before her death in 1905, at the age of eighty-two, she had become a beacon of strength, faith, and wisdom to her family and everyone that knew her. One of her sons, George William Mathews, became a minister and served at St. Luke in Columbus. His son, George Mathews, Jr. was a prominent businessman in Columbus and raised his children here. There are other descendants of Tryphena, and the Williams-Moore family, who continue to call Columbus their home today. Her legacy as a comforting light, created in the darkest pit of despair, lives on amongst her progeny. On Tryphena’s gravestone, her final epitaph reads: “Her children arise up, and call her blessed.”